Testing for Parkinson’s disease may one day be as easy as a simple skin biopsy.

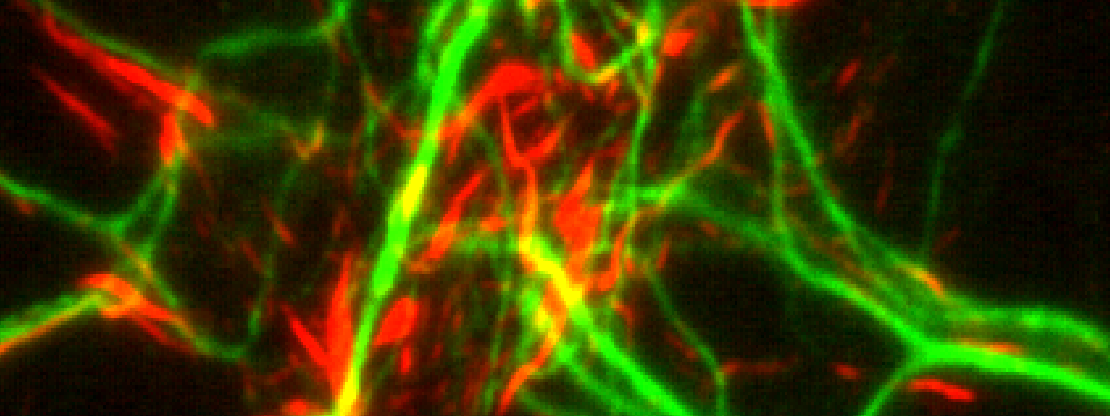

That’s because the disease, like most villains, leaves behind clues as it moves through the body. In this case, the evidence takes the form of alpha-synuclein, an abnormal protein closely linked to Parkinson’s that aggregates in nerve cells within the skin.

“Right now, we do not have a totally effective, objective way of diagnosing Parkinson’s, particularly in its early stages,” said Jiyan Ma, Ph.D., a professor at Van Andel Institute. “Developing such a test would be a game-changer, in terms of treatment, tracking disease progression and assessing therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials.”

Diagnosing Parkinson’s early on is notoriously difficult; the disease often isn’t caught until the appearance of movement-related symptoms, a sign that it is already advanced. These symptoms typically prompt a visit to the doctor’s office, where physicians must rely on set clinical criteria and responses to Parkinson’s medication for diagnosis.

Other methods, such as analyzing spinal fluid obtained through a spinal tap, are invasive and painful. Brain imaging or blood tests still lack the sensitivity and specificity to achieve a solid diagnosis.

“Parkinson’s is an elusive foe in many ways,” Ma said. “But now, technology is helping us catch up.”

For the last year, Ma has been collaborating with Wenquan Zou, M.D., Ph.D. and Shu G. Chen, Ph.D. at Case Western Reserve University. Using proteins provided by Ma’s lab, Zou, Chen and their team found that an ultra-sensitive test called real-time quaking-induced conversion could be used to accurately detect alpha-synuclein in autopsied skin samples from people with Parkinson’s. The findings were confirmed by Ma’s lab using a test they developed called protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA).

Now, thanks to a five-year, $3.6 million National Institutes of Health grant, the team will be able to expand their study to include a larger number of samples, a critical step in validating the approaches for use in the clinic. They also have teamed up with Thomas Beach, M.D., Ph.D., from Banner Sun Health Research Institute and Steve Gunzler, M.D., from University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, who will contribute samples to the study.

At this stage, the team is verifying the test’s ability to consistently and accurately detect alpha-synuclein in the skin. Later, they plan to test people at varying stages of Parkinson’s to see if alpha-synuclein can be used as a biomarker to measure and track disease progression. If successful, it would give scientists a powerful new tool to evaluate the effectiveness of new medications designed to slow or stop disease progression, something not possible with current treatments.

“Right now, we can only treat symptoms, not stop progression,” Ma said. “It is our hope that this test will give us a way to detect Parkinson’s much earlier in the disease process while also giving scientists a much-needed tool for evaluating new therapies that actually treat the root cause of Parkinson’s and slow or even stop it.”

To learn more about Ma’s research, visit malab.vai.org. You can find additional information on Parkinson’s disease and VAI’s research at vai.org/parkinsons-disease.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers 1U01NS112010-01 (Zou, Chen, Ma) and R21NS101676 (Ma). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

What is Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s is a progressive, neurodegenerative disorder that affects 7 million to 10 million people worldwide. Its hallmark motor symptoms include tremor, freezing and stilted gait. Non-motor symptoms, such as constipation, loss of sense of smell and depression, may precede motor symptoms by years or even decades.